The choice between demolition or reuse: developer insights

Background

It is often the case that simple ideas are the best ideas, and this holds true when it comes to reducing the impact of the built environment. From a numerical perspective, the impact of the industry is staggering – approximately 40% of the UK’s emissions are attributable to the built environment, while construction, demolition, and excavation activities generate approximately 60% of the UK’s waste[1]. When a building is demolished and a new one is put in its place, the emissions locked into the original building are wasted and the new building’s material manufacturing and construction processes create new emissions. Even energy efficient buildings can take decades to save more operational energy emissions than were created in the construction process up to 51% of a residential building’s carbon is emitted before the building is operational (and up to 35% for an office building).[2]

So, the solution to rampant emissions and waste seems simple – let us reuse existing structures and materials. Without a vested interest by the built environment industry in retention over demolition, the sector is unlikely to decarbonise and reduce emissions according to its impact. This is why “Maximise Reuse” is one of the five guiding principles in UKGBC’s Circular Economy Guidance for Construction Clients (see Figure 1)[3]. Some industry professionals are likely to tell you that the idea is deceptively simple and that there are multiple barriers in the way that somehow justify demolishing 50,000 buildings a year in the UK [source][4]. Without better understanding the choice between demolition and reuse, and factors influencing the thinking process towards reuse, we cannot advocate for the tools, resources, and policies needed to make reuse the industry default.

The Maximise Reuse principle. Image taken from the UKGBC Implementation Pack for Reuse.[5]

This analysis focuses on A and B from the “Maximise reuse” principle, as displayed in the image above. The terms reuse and refurbishment are used interchangeably but is it acknowledged that these can be two different processes.

UKGBC interviews

UKGBC is a partner on CIRCuIT – Circular Construction in Regenerative Cities – a collaborative EU Horizon 2020 project involving 29 ambitious partners across the entire built environment chain in Copenhagen, Hamburg, Helsinki Region and Greater London. CIRCuIT is addressing the challenges of reuse in its ‘Extending Lifecycles’ workstream, which aims to enable transformation and refurbishment in cities through investigating innovative design strategies, principles and methodologies. UKGBC is contributing to data collection in support of these aims, in part by interviewing nine leading developers within the UKGBC member network, to gather their insights into decisions to demolish or reuse buildings. The results will feed into the development of an evidence-based systematic methodology to identify obsolete and transformable buildings and help the project to create replicable design strategies and principles that encourage transformation over demolition.

UKGBC is sharing some highlights from these interviews, in the hope that they can shed additional light on the reuse landscape in the UK and identify where barriers emerge. We intend the results to help inform future studies and policy decisions and enable developers to compare their reuse processes with wider industry. This article will cover interviewee responses to the following questions:

- When does your organisation define a building as obsolete?

- What are the key factors guiding your decision to demolish or refurbish a building?

- What might change your decision to demolish or refurbish a building?

- Do you have any key insights into this topic, gleaned from your own project portfolio?

Quotes have been anonymised.

What makes a building obsolete?

“The process of defining obsolescence is becoming more complex as we try to bring more factors into account: how do you balance these things to make the perfect decision?”

Interview #3

While definitions can help steer organisational decision-making, there was a general acknowledgement across our interviewees that creating a static definition for “an obsolete building” was unrealistic and perhaps even unhelpful. Given the range of building types and project contexts within and between our developers’ portfolios, most dealt with the question of obsolescence on a case-by-case basis, focusing on whether buildings were ‘fit for intended purpose’. Some common themes emerged within this, specifically, when the limit had been reached for factors such as:

- Income generating possibilities for the developer;

- Structural soundness, material quality and aesthetic appeal (e.g. the condition of mechanical and electrical (M&E) services and finishes);

- Occupant safety and a comfortable internal environment.

The distinction between structural obsolescence and M&E obsolescence was noted by two developers, particularly in sectors like healthcare, where outdated M&E connections can render reuse impossible due to the difficulty and expense in frequently upgrading older systems to meet modern codes and regulations. However, as the structure is composed of a large myriad of components and parts, one interviewee argued that reuse of some components of a building should always be an option, unless the structure was completely decrepit.

Something that divided the interviewees was their default strategy when beginning a new project on an existing building site. Five developers informed us that they always considered refurbishment to be worth assessing and thus had mechanisms to understand and present the business and environmental case. The other four developers tended to default to an assumption that a new build would be most cost effective and practical, unless reuse was a regulatory requirement (e.g. for listed buildings). The developers who viewed reuse as an equally viable option to demolition and, critically, had strategies to promote refurbishment in the early project stages had more reuse projects within their portfolios. This highlights the importance of integrating reuse principles into the project conceptualisation stage.

Key factors guiding a choice to demolish or reuse

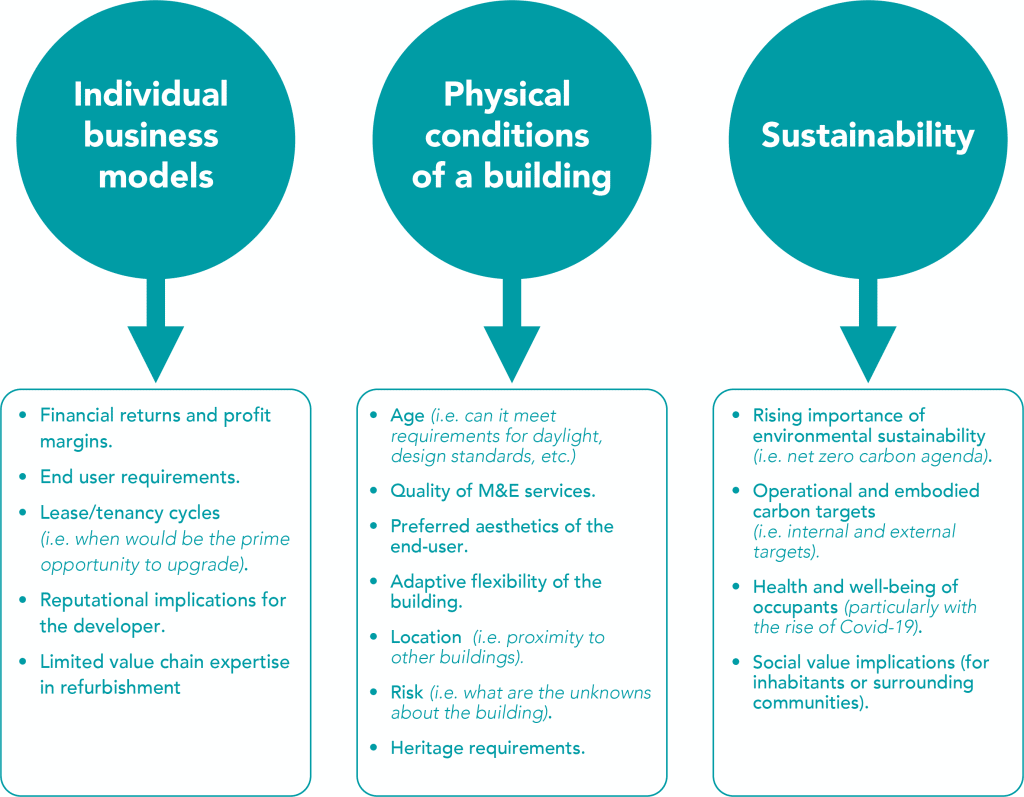

To gain more insight into the specific factors leading to demolition or reuse, we asked the developers to expand on the key factors that could sway this decision. The factors identified can be broadly split into the following three categories:

The factors were diverse, and their value to our interviewees varied, but three are worth expanding on:

Financial returns

Unsurprisingly, forecasted financial returns on investment factored significantly into the decision-making process for every developer. While each interviewee acknowledged the rising importance of the ESG agenda on their projects, and that purely financial metrics were decreasing in significance, the final decision-makers (generally investors and board members) were unlikely to provide their support for any refurbishment works without being presented with a positive financial business case.

One interviewee described how, despite the fact their organisation had adopted multiple ESG principles for their company’s strategies and projects, financial metrics would still weigh in at about 40% of the final decision.

“Financial returns will always play a big role, but the industry is moving towards trying to deliver value, not just financially, but also from a social, health and well-being perspective.”

Interview #8

Another developer acknowledged that the only factor that might out-weigh costs would be very strict heritage requirements to retain a building, or parts of it. Brownfield land tends to be cheaper and without a detailed and full record of the building, it can be difficult to estimate the damages. The potential for costs to accumulate during reuse projects was also flagged as difficult to account for, with two developers tending to err on the side of caution when valuating projects because of uncertainty. Reuse is thus not always the cheaper option.

Environmental and social sustainability

Rising awareness of the built environment sector’s impact on the climate, and our ability to meet net zero carbon legislation in the UK, has increased the pressure on developers to reduce their impact. Most developers interviewed had set ambitions for operational energy performance metrics and reductions in embodied carbon emissions on their projects, with some setting net zero targets using frameworks like the UKGBC Net Zero Carbon Buildings definition[6]. It was acknowledged by several interviewees that implementing circular principles, such as the reuse and refurbishment of buildings, was an increasingly popular mechanism to meet these goals, particularly for the reduction of embodied carbon.

However, some acknowledged that this link could be tenuous and further evidence was needed to ensure there would be no unintended consequences of increasing carbon. Two developers questioned whether it would always be the case that a refurbished building could meet operational emissions and social value targets, even if embodied carbon were reduced compared to a new build. While certainly not a reason to discount refurbishment, the life cycle link between reuse and embodied carbon must be considered.

“There could come a tipping point where sacrificing some embodied carbon to rebuild something that is going to be operationally more efficient and a nicer place to be (in terms of well-being and social value) will create a more compelling argument for demolition than refurbishment.”

Interview #3

Interestingly, two of the developers whose, ‘business as usual’ approach for projects was to demolish and build new, still acknowledged that they expect to increasingly be required to consider refurbishment from the onset, with ESG considerations gaining quick traction and support. Financial investors are increasingly demanding proof of climate resilience within physical assets and wider portfolios, alongside increasingly engaged occupiers demanding high-quality, sustainable work and living spaces, thus providing additional incentives for developers to refurbish. These increasingly prominent environmental demands and drivers from actors throughout the value chain are shifting company priorities.

Social value was also cited as rising in prominence, but approaches to including social factors in option appraisals for projects differed. Although increasingly being called for by investors and occupiers, three developers described the difficulty in quantifying social value, some saying it just did not factor into their decision-making at all due to a lack of consistency, comparability, and reliability in metrics and valuation tools on the market.

Building risk

Limited information about the structure or constituent materials of an existing building could, from the offset, impede the potential for reuse. Structural safety was highlighted by our interviewees as a key factor underpinning potential obsolescence of a building, and the comprehensive surveys required to assess the level of risk in reusing an older building might not always be financially feasible or possible within the time constraints of a project. One developer notably acknowledged that there were often unforeseen safety problems that emerged only once the refurbishment project was underway. This reduced the incentive to consider reuse in the project given the increased management costs.

Change levers

With return on investment still fundamentally underpinning decisions, the challenge is to better account for, and quantify, more intangible factors to better link reuse to wider ESG goals and demonstrate the value of existing assets. Changing market forces, climate resilience, embodied carbon, and social impact, amongst other factors, can greatly influence the decision to refurbish or demolish, with potential to positively swing the pendulum towards reuse in many cases. Interviewees identified two distinct categories where change levers could emerge to encourage reuse:

Knowledge and supply chain gaps

Our interviewees consistently called for clearer ways to identify and quantify the benefits of reuse. Additional levers suggested to address knowledge and supply chain gaps include:

- Improved demonstration mechanisms (e.g. case studies) to show how climate resilience can be attained through refurbishment, to better make the case to financial investors; more case studies demonstrating the best practice approaches to refurbishment and data on the business case for them.

- Clarity over how reuse/circularity can support net zero carbon ambitions and other ESG goals and reporting frameworks e.g. SBTs, TCFDs, etc.;

- Higher quality and quantity of information and data on materials within existing buildings through the use of tools like material passports. This would enable the industry to better understand issues surrounding warranty, safety, and compliance with building regulations when undertaking refurbishment and material reuse. Digitalisation of such information was thought to be key to ensuring reuse at the end of a building’s life cycle;

- Improved technologies to make material reuse more practical and avoid over-design; and,

- Improved training, skills and understanding about refurbishment and adaptive reuse processes.

Difficulty in understanding potential safety and quality issues when it comes to reusing existing building structures and materials was arguably identified as the key barrier restricting refurbishment. Interviewees acknowledged that although there is no simple approach to address this for our current building stock, we should learn from experience and identify this as an opportunity to design out such problems in our new buildings by employing novel approaches such as material passports. An effort by market leaders and government to encourage innovative technologies, such as using material exchange platforms like Madaster in the UK, could help create a significant market shift.

Policy, regulations, and reporting

The early stages of a project are critical for embedding reuse into its strategy and ethos, with the viability of reuse becoming increasingly challenging as a project progresses. One common strategy to promote reuse put forward by our interviewees was a requirement to demonstrate in planning applications why a building and its materials cannot be retained before permitting demolition. Shifting starting assumptions so that all buildings are assessed from the same perspective can incentivise innovation where otherwise demolition might have been the status quo. The importance of incentives was also highlighted, with one interviewee citing that this would be preferable to regulation. Currently, there are few incentives in the planning process to encourage developers to retain buildings.

“Incentivisation is more powerful than legislation and would be preferred. Legislation adds further delays to planning.”

Interview #4

Additional recommendations included:

- Reducing the 20% VAT rate for refurbishments so it is on par with new builds or lower

- Faster planning application processing for projects including reuse at significant scales

- Consistent definitions and rules across councils and governments (ex. for heritage retainment requirements).

Importantly, it was acknowledged that any changes to planning or legislation ought to come with increased training for authorities to properly assess applications so that they acknowledge the potential challenges or knock-on implications of reuse and refurbishment. For example, retaining a building’s original superstructure can make meeting operational energy requirements more costly or challenging, or the required number of units/dwellings may become unfeasible to deliver.

For more info on policy recommendations, see the UKGBC Circular Economy Policy Asks.

Conclusion

CIRCuIT is seeking to tackle some of the barriers we have explored within this blog by producing methodologies and case studies that make it easier to assess the reuse potential of buildings from the outset, and by demonstrating the business and environmental case for refurbishment. Nevertheless, this can only go part of the way towards addressing these challenges. Three final thoughts offered by the developers we interviewed further highlight opportunities to enable a wider sectoral shift:

- Increasingly, requirements are emerging (be they regulatory, client or occupier driven) to start considering refurbishment before deciding to build new. The market is moving this way because of the increased focus on net zero carbon and other sustainability aspirations. Developers who do not put in the effort now to plan projects with reuse in mind risk falling behind.

- You can only learn from beginning this process. Reuse is inherently less straightforward than demolishing and building from scratch. Yet developers stand to gain from a unique product offering, embodied carbon savings, positive social value impact and more. We require more demonstrations of successful and profitable refurbishment to help enable other developers to follow suit with confidence.

- Setting a net zero vision and challenging project teams from the earliest stages is critical. Ultimately, it is developers and investors who hold the cards and need to grant their design and construction teams the permission to innovate. UKGBC’s “Unlocking the delivery of net zero buildings” provides more guidance on setting the initial project brief and ensuring a net zero or circular vision can be implemented throughout project delivery.

The CIRCuIT methodology will be published in 2021.

Additional reading

- Circular Economy Implementation Packs for Reuse and Products as a Service

- Circular economy guidance for construction clients: How to practically apply circular economy principles at the project brief stage

- Circular economy actor and resource map

- Circular Economy Policy Asks May 2020

- Delivering Social Value: Measurement

- Circular Economy Forum

- BRE Sustainable Refurbishment Briefing Paper

References

[1]UK Government (2020), UK Statistics on Waste: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/918270/UK_Statistics_on_Waste_statistical_notice_March_2020_accessible_FINAL_updated_size_12.pdf

[2] BBC (2020), Don’t demolish old buildings, urge architects: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-53642581

[3] UKGBC (2019), Circular Economy Guidance for Construction Clients: https://ukgbc.org/resources/circular-economy-guidance-for-construction-clients-how-to-practically-apply-circular-economy-principles-at-the-project-brief-stage/

[4] Architects Journal (2019), Introducing RetroFirst: A new AJ campaign championing reuse in the built environment: https://www.architectsjournal.co.uk/news/introducing-retrofirst-a-new-aj-campaign-championing-reuse-in-the-built-environment

[5] UKGBC (2020), Circular Economy How-to Guide: Reusing Products and Materials in the Built Environment: https://ukgbc.org/resources/circular-economy-implementation-packs/

[6] UKGBC (2019), Net Zero Carbon Buildings: A Framework Definition: https://ukgbc.org/resources/net-zero-carbon-buildings-a-framework-definition/

Related

Taking Action for Consistent Early-Stage Embodied Carbon Measurement

Challenges and Opportunities in Commercial Retrofit

NZWLC Industry Pulse Check: Whole life carbon measurements and agreed limits

Impactful offsetting: using regenerative farming to generate carbon credits